AA-3 BFM Terms and Training Rules

2.0 hrs

Objectives

1. BFMDescribe the fundamentals /of principlesBFM.

2. Describe the principles of BFM.

3. Describe the plane of the defender.

4. Explain aircraft separation.

5. Explain an overshoot.

6. Explain the concept of line of sight (LOS) rate.

7. Explain the BFM tools.

8. Explain BFM brevity code words and concepts.

9. Explain the BFM training rules (TRs).

Assignment

1. Review Lesson AA-3 in the Basic Fighter Maneuvers Student Guide, B/F-V5A-K-AA-SG.

2. Read MCMAN 11-238, Vol 2, Chapter 3, Offensive Maneuvering. Read AFI 11-214, Air–to–Air Training Rules.

Information

Fundamentals of BFM

Objective 1 — Describe the fundamentals of BFM.

1. Golden rules

a. Lose sight, lose fight — You must detect the bandit early enough to defeat the bandit’s weapons. On offense

you must keep sight so that you can predict the bandit’s flightpath and maneuver to the weapons employment zone.

b. Maneuver in relation to the bandit — While maneuvering to the WEZ you must solve range, aspect, heading

crossing angle (HCA), and closure problems generated by the defender’s maneuvering. You must create BFM

problems that the attacker cannot solve when on defense. In either case, you must maintain awareness of the

bandit’s position and orientation to the earth so you can create or solve BFM problems with radial–G assistance

(make the bandit maneuver in relation to you).

c. Nose position vs. energy — The ability to maneuver offensively or defensively is directly related to your

energy state. It takes energy to climb, turn or accelerate. The BFM challenge is to manage energy in properly timed

maneuvers that solve problems. You may cash in energy to point your nose to employ weapons or negate

immediate threats.

Principles of BFM

Objective 2 — Describe the principles of BFM.

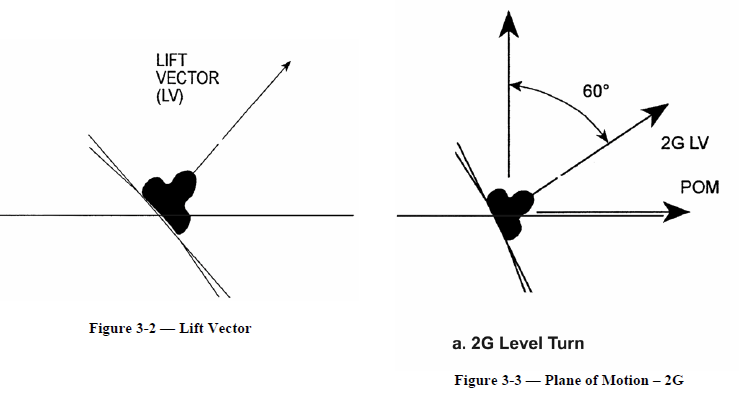

1. Roll — When you roll the airplane you are “setting” or “pointing” the lift vector (LV) (thus determining the POM

in which you will turn). The fastest way to change the T–38 lift vector is an unloaded roll at zero–G.

a. An important aspect of roll is the ability to slow the aircraft’s forward velocity if G is maintained.

b. A second benefit of roll is the ability to maintain “tally” (discussed further in the Offensive Maneuvering

lesson’s HAGS exercise — use of roll to maintain “tally” versus energy depleting kick–outs).

2. Turn

a. After the LV is set, the airplane is turned with the application of G. As we saw in Advanced Handling, turn

rate and radius is a function of true airspeed and G.

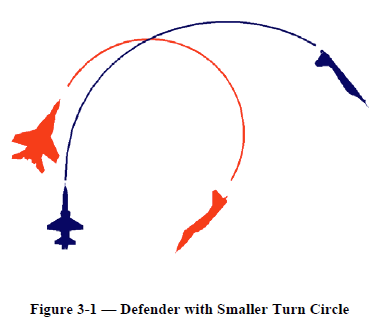

b. Aircraft turn radius defines an aircraft’s turn circle. The defender’s goal is to have a turn circle small enough

to exclude the attacker. The attacker’s goal is to get into the defender’s turn circle.

c. You must have energy (airspeed) to make the aircraft turn (move the nose) to kill on offense.

d. On defense, you must be able to turn to move the

tail so as to deny the bandit weapons parameters.

e. Sustained offensive operations in the same plane

against a defender who has a smaller turn circle is not

possible without inviting an overshoot/reversal

situation (Figure 3-1).

f. In general, when the attacker is outside the

defender’s turn circle aspect angle increases. When

inside the defender’s turn circle aspect decreases or

remains constant.

g. You are outside the bandit’s turn circle if the

bandit’s present rate of turn brings you forward of the

defender’s 3/9 line, i.e., long range BFM. You are

inside the defender’s turn circle when the defender’s

rate of turn will not bring you forward of the 3/9 line,

i.e., short range BFM.

3. Acceleration maneuver

a. The acceleration maneuver in Advanced Handling demonstrated aircraft performance. Now we must consider

the BFM affects of the acceleration maneuver.

b. Acceleration is used to increase airspeed for maneuverability or to increase/decrease slant range to a bandit.

c. G–load — The T–38 is fastest at zero–G but the nose will drop in free–fall. Remember not to bury the nose.

d. Bank — Bank has no affect on acceleration, but you must consider the aircraft profile so as not to “flash

away” your position.

e. Pitch — You can speed fastest with the nose below the horizon.

f. Airspeed — The faster you go, the faster you go faster.

g. Density altitude — The denser the air the better the acceleration (low altitude).

3. Acceleration maneuver

a. The acceleration maneuver in Advanced Handling demonstrated aircraft performance. Now we must consider

the BFM affects of the acceleration maneuver.

b. Acceleration is used to increase airspeed for maneuverability or to increase/decrease slant range to a bandit.

c. G–load — The T–38 is fastest at zero–G but the nose will drop in free–fall. Remember not to bury the nose.

d. Bank — Bank has no affect on acceleration, but you must consider the aircraft profile so as not to “flash

away” your position.

e. Pitch — You can speed fastest with the nose below the horizon.

f. Airspeed — The faster you go, the faster you go faster.

g. Density altitude — The denser the air the better the acceleration (low altitude).

Plane of the defenderDefender

Objective 3 — Describe the plane of the defender.

1. Application — To apply the roll, turn, accelerate mechanics of BFM we need to understand bandit plane of motion

(POM).

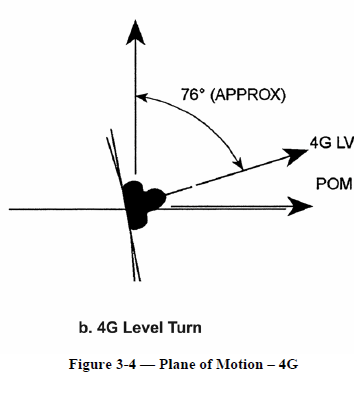

2. There are two planes — plane of symmetry (POS) and POM.

a. Think of POS as where the lift vector (LV) is oriented. You may think of the LV as an extension of the

vertical stab or envision the LV as the view out the top of the canopy (Figure 3-2).

b. POM — Plane extending from the flightpath of an aircraft to the center of its turn radius (Figure 3-3 and 3-4).

3. As G–load increases, POS and POM converge. Both attackers and defenders must assess where their adversary is

going; in other words their adversaries POM.

4. BFM application — To take a gunshot, observe the defender’s POM and predict where the aircraft will be as you

maneuver to the gun WEZ.

Aircraft Separation

Objective 4 — Explain aircraft separation.

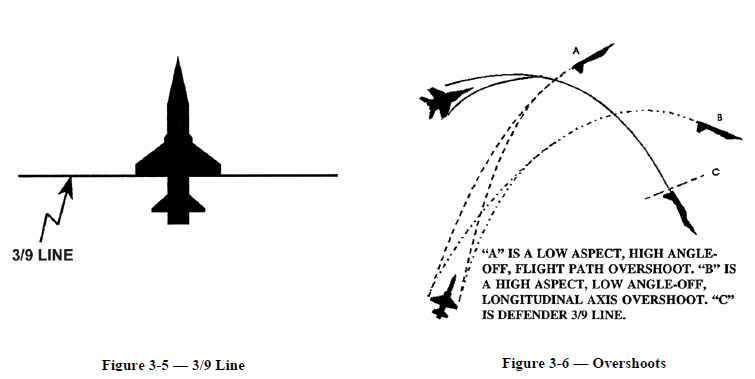

1. Aircraft separation /is multi-dimensional

a. Vertical — Altitude separation

b. Lateral — Horizontal separation

c. Nose-tail — When the attacker is behind

the defender’s 3/9 line the attacker has a

positional advantage (Figure 3-5).

d. Slant range — A numerical combination of

all aircraft separation.

2. Turning room — Displacement from the

adversary’s flightpath in any POM that you may use

to reduce aspect angle and HCA.

Overshoots

Objective 5 — Explain an overshoot.

1. Flightpath and 3/9 overshoots4.a. Flightpath — Flying to the outside of the turn circle increases the length of your flightpath thus enabling you

to stay behind the defender’s 3/9 line while maintaining energy. You also gain some lateral turning room (Figure

3-6).

b. 3/9 outside of turn circle — If closure is not controlled by the flightpath overshoot your vector may take you

in front of the defender’s 3/9 line and force you to defend.

c. 3/9 inside of the turn circle — Too much lead pursuit may force you to overshoot.

d. 3/9 straight-ahead — Failure to control airspeed could put you on the defense.

Line of Sight

Objective 6 — Explain the concept of line of sight (LOS).

1. The definition of LOS is the angular rate in degrees per second that the bandit is moving across the canopy.

2. The LOS elements are range, aspect angle, heading crossing angle, target speed, and target G. Note that the

discussion of each element assumes all other elements remain the same. In use they all act in conjunction.

3. Slant Range

a. As the slant range decreases, LOS rates increase.

b. As the slant range increases, LOS rates decrease.

4. Aspect Angle

a. As aspect increases, with closure, LOS rates increase.

b. Maximum LOS rates occur on the 3/9 line.

5. Heading crossing angle (HCA)

a. As heading crossing angle (angle–off) increases, LOS rates increase (maximum rate at 180°).

6. Target speed

a. As target speed increases LOS rates will increase.

b. Maximum effects at 90° aspect

c. Minimum effects at zero or 180° aspect

7. LOS rate for target–G and aspect

a. As target-G increases, LOS rates will increase. The highest G effects will occur at 0/180° aspect and heading

crossing angle. Target–G effects are minimum on the 3/9 line.

b. In general, when attacking a defender from a position of advantage you will have to reduce aspect so that you

can turn with him.

8. LOS vs. range and aspect

a. As slant range decreases at a given aspect, rates increase. As LOS increase the attacker’s rate of turn (ROT)

must increase.

b. If the attacker’s ROT is larger than the defender’s LOS then the attacker can pull lead.

c. If the attacker’s ROT is equal to the defender’s LOS then the attacker can only pull pure pursuit.

d. If the attacker’s ROT is less than the defender’s LOS then the attacker is forced into lag pursuit.

e. Example: At 30° aspect the LOS is 5°/sec at 4,500 ft slant range (assume attacker ROT of 10°/sec). The

attacker’s ROT exceeds the LOS and the attacker may pull lead. At 30° aspect and 1,900 ft slant range ROT

required equals LOS which means the attacker can only pull pure pursuit. At 1,000 ft slant range LOS is 15°/sec

but the attacker’s ROT is limited to 10°/sec, thus forcing lag pursuit.

f. Example: At 60° aspect the LOS is 4°/sec at 8,000 ft slant range. The attacker’s ROT exceeds the LOS and

may pull lead. At 60° aspect and 3,500 ft slant range ROT required equals LOS, which means the attacker can only

pull pure pursuit. At 2,100 ft slant range LOS is 15°/sec but the attacker’s ROT is limited to 10°/sec, thus forcing

lag pursuit.

g. Application: How do you use this data to solve BFM problems? If you need lead pursuit to generate closure,

then you must pull it at a range where ROT exceeds LOS. To pull lead at shorter slant ranges you must reduce

aspect angle with BFM maneuvers.

9. LOS vs. the collision course

a. LOS on a collision course is zero.

b. Nose position ahead of the collision course generates an aft LOS movement.

c. Nose position behind the collision course generates a forward LOS movement.

10. LOS vs. turn circle

a. Defender sees forward LOS if attacker is outside the defender’s turn circle.

b. Defender sees aft LOS if attacker is inside the defender’s turn circle.

BFM Tools

Objective 7 — Explain the BFM tools.

1. BFM tools

a. Power/energy management

b. Pursuit curves

c. Out–of–plane maneuvering

2. Power/energy management

a. You must have airspeed to climb/turn/accelerate.

b. Kinetic energy is a function of mass and true airspeed. Usually we think in terms of calibrated airspeed

because of the ease of reading the airspeed indicator and because aircraft limits are commonly defined in these

terms.

c. Use throttle modulation to increase or decrease airspeed and thus increase or decrease closure.

d. Increase drag to reduce airspeed and thus reduce closure. Open or close the speed brake as necessary to control

airspeed changes.

e. Vary G–loads to affect airspeed changes. This is important when trying to max perform your aircraft.

f. Rate and radius of turn depend on true airspeed and G–load.

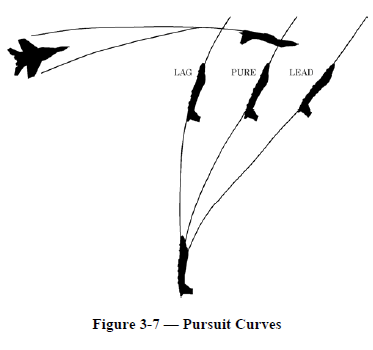

3. Pursuit curves (Figure 3-7) — Geometric closure generated

or controlled by selecting a pursuit curve. Your energy/G and

POM will determine closure rates, aspect, and heading crossing

angle.

4. BFM operations include lead, pure and lag pursuit. The

T-38C zero mil reference (center of HUD TFOV) tells us where

our aircraft is pointed (i.e., our pursuit course).

a. Lead pursuit

(1) Your nose is pointed in front of the defender.

Lead pursuit increases closure, maintains or increases

aspect angle, and may set up a gunshot opportunity.

(2) Aspect angle increases. This is a penalty you pay

to gain closure. If the attacker establishes too much

lead, the attacker might fly in front of the defender’s

3/9 line.

(3) HCA decreases. It may be to your advantage to

have the fuselages aligned. During a turning rejoin you

are applying the principles of lead pursuit.

(4) An initial lead pursuit attack is driven to lag if the attacker has insufficient turn rate available to maintain

lead.

b. Pure pursuit inside the turn circle

(1) Your nose is pointed at the defender.

(2) Closure is positive but less than lead because your flightpath is slightly longer.

(3) Aspect angle increases until you reach limit–G then you are forced into lag pursuit. If you have a low–G

target or if you have the ability to pull high–G, then pure pursuit will fly you into low aspect and low heading

crossing angle.

(4) Defender sees an aft line of sight.

c. Pure pursuit outside the defender’s turn circle

(1) Aspect and heading crossing angle increases.

(2) Defender sees the attacker moving forward in the canopy.

d. Lag pursuit

(1) Your nose is pointed behind the defender. Closure decreases.

(2) Aspect angle decreases until you cross the bandit’s 6 o’clock then increases.

(3) Heading crossing angle increases because you are turning away from each other.

(4) Lag pursuit can build turning room, decrease aspect angle, and control overtake (Turn circle entry

discussed in Offensive Maneuvers). Excessive lag does remove pressure on the bandit.

e. Pursuit curve summary — Which curve should you use?

(1) In general, lead and lag are good BFM solvers.

(2) Pure pursuit is not real good at solving BFM problems. It is good for tactical deception and weapons

employment.

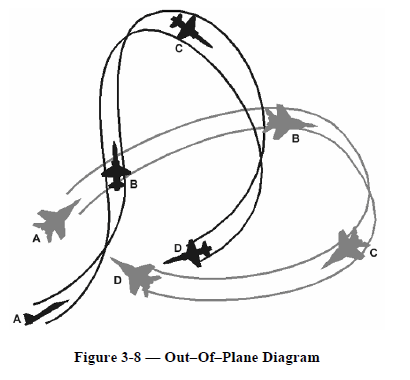

5. Out–of–plane (OOP) maneuvering.

a. When the attacker is out of the defender’s plane of turn, the pursuit course is determined by where the

attacker’s present lift vector (LV) (top of the canopy) will position the aircraft as the attacker enters the defender’s

plane of turn.

b. OOP gains turning room when the

defender’s turn radius will not permit staying

in-plane. OOP maneuvering also controls

overtake.

c. Excessive OOP maneuvering can remove

pressure on the bandit, allow an extension, or

present the defender turning room which can be

used against the attacker.

d. The key at point C (Figure 3-8), on the

out–of–plane diagram, is to be sure you enter

the defender’s turn circle aft of the wingline

with the ability to establish an in–plane lead

pursuit course at point D.

6. Lag BFM — Also known as “Canopy Bow”

BFM. Attacker maneuvering based on defender turn

circle. Also, how the defender line of sight rates are

viewed from the attacker’s canopy bow. If not in a

position to employ ordnance now, the attacker’s

goal during offensive maneuvering is to drive to the

bandit’s turn circle, reduce aspect, and control line–

of–sight (the control position — approximately

2,500 ft–4,500 ft behind the bandit, low aspect, nose slightly in lag). On defense, an attacker may attempt to “square the

lag corner” to employ weapons or continue the attack.

Code Words and Concepts

Objective 8 — Explain BFM brevity code words and concepts.

1. Prior to flying your first BFM missions you should have a solid understanding of the following brevity code words

and BFM concepts.

2. Why use code words and brevity?

a. Common language, minimize confusion in training or combat (multi-service).

b. Transmissions must be brief because radio frequencies will be saturated or degraded. Too much unessential

chatter and an important “Break” call doesn’t get passed.

3. Know the following code words:

a. Blind — No visual contact with friendly fighter

b. No Joy — No visual contact with the target/bandit

c. Tally — Sighting of a bogey/bandit

d. Visual — Sighting of a friendly aircraft

e. Engaged — Maneuvering with the intent of achieving a kill or negating the threat. If no additional

information is provided, “engaged” implies visual/radar acquisition of the threat.

f. Hard (direction) — High–G energy sustaining turn

g. Break (direction) — Directive to perform an immediate maximum performance turn in the indicated

direction. Assumes a defensive situation.

h. Defensive — Aircraft is in a defensive position and maneuvering with reference to the stated condition. If no

condition stated, maneuvering is in respect to an air–to–air threat.

i. Fox I (1), II (2), III (3) — Firing of Air-to-Air weapon (radar missile, heat seeking missile, guns).

j. Jink — Directive call for aircraft to “jink” due to a bandit entering the friendly’s WEZ.

k. Flare — Directive to dispense countermeasures or information that chaff/ flares are being dispensed.

4. The following BFM concepts are valid during all fighter maneuvering, yet they may be applied differently based

on the training/combat situation. For example, the ground or AAA range may be the minimum altitude in combat while

the Air Combat Training (ACBT) floor is your minimum altitude in training.

a. BFM cross–check — Fighter pilot ability to analyze aircraft airspeed, G, altimeter and LV in relationship to

the bandit. An effective BFM cross–check maximizes your aircraft’s capabilities during both offensive and

defensive maneuvering.

b. Floor transitions/floor saves — You must include floor awareness in both offensive and defensive air–to–air

game plans. In many cases high performance maneuvering is also energy depleting. As a result, you may only

trade altitude loss to sustain turn capability down to the ACBT floor or ground.

c. “Energy” fight versus “Nose Position” fight — As an attacker or defender it is important to assess whether

your adversary is attempting to fight an “energy/rate” fight or a “cash it in/nose position” fight.

Attackers/defenders may fight in only one of these spectrums, a combination of these spectrums or transition from

one spectrum to the other.

Training Rules

Objective 9 — Explain the BFM training rules (TRs).

1. You cannot play the game unless you know the rules.

2. The training rules are located in AFI 11-214. You must know the rules and instructions (operating procedures,

TRs, ROE, etc) and be able to recall them from memory without hesitation. The rules were developed over the years to

enhance flight safety and to promote efficient training.

3. Special Operating Instructions

a. Training rules are briefed for each sortie.

b. Video cameras are used and assessed.

c. Supersonic flight only in designated areas.

d. Safe fuel minimums are established and briefed.

e. “Ops checks” are made prior to each engagement.

f. Debriefings are professional and critical.

g. Mutual support requirements are briefed.

4. Unlimited maneuvering category

Unlimited is the normal air–to–air training maneuvering category for IFF. No restrictions except AFI 11-series and

Flight Manual aircraft limits.

5. Weather

a. 2,000 ft vertical

b. 1 nm horizontal cloud clearance

c. 5 nm inflight visibility

d. Clearly discernible horizon

6. Minimum altitudes (IFF)

a. 5,000 ft AGL dual

b. 10,000 ft AGL solo

c. Convert AGL to MSL in the area so that you can comply with the restrictions based on an MSL altitude.

7. Separation of aircraft

a. 1,000 ft vertical separation until “tally” or situation awareness determines that your opponent is not a collision

factor. 1,000 ft min slant range during the attack.

b. If visual contact is lost, how do you establish separation? Example, “Talon 1 blind,” “Talon 2 blind at 16,000

ft,” leader will then be directive.

c. If attacker loses sight, maneuver away from defender’s last known position and call “no-joy/blind.”

d. If defender loses sight call “no-joy/blind” and maneuver predictably.

e. If approaching head–on; clear right but do not cross flightpaths. 9,000 ft min range head–on missile shot.

f. Gun attacks — no greater than 135°.

8. “Knock-It-Off” (KIO)/Termination situations

a. When safety of flight is a factor.

b. Dangerous situation developing. (When doubt or confusion exists)

c. Situation awareness lost.

d. Weather below minimums (Altitude or cloud clearance a factor).

e. Maneuvering limits are reached (Over–G, min airspeed, etc.).

f. Bingo or minimum fuel

g. Any unbriefed/unscheduled flight in area

h. Learning objectives achieved.

i. Stalemate

j. Radio failure is recognized.

k. Any aircraft continuously rocks its wings.

l. Approaching an area boundary

m. Training Rules or other limits exceeded.

n. Anyone calls “Knock-It-Off”/ “Terminate”.

Review Exercise 3

Complete the following review exercise. Answers are in the back of the SG.

1. Which pursuit curve creates the most closure (assume all other conditions are constant)?

a. Pure

b. Lead

c. Lag

d. Direct

2. The fastest roll rate in the T–38C is achieved at Gs.

3. Line–of–sight rate is a function of which five things?

4. What are the three fundamentals of BFM? __________________________________

5. __________ is airspace in the vertical, horizontal, or both, which can be used to solve aspect/heading crossing

angle (HCA) or to execute a desired maneuver.

6. What are the three BFM tools? ________________________________

7. Match the following terms with their definitions:

_____ Heading crossing angle A. An unidentified aircraft, friend or foe

_____ Aspect angle B. Prebriefed fuel state above bingo

_____ Bandit C. Offensive or defensive aircraft making the bandit predictable

_____ Bogey D. Angular difference between the longitudinal axis of two aircraft

_____ Lead turn E. Bandit in sight

_____ Defensive turn F. Enemy aircraft

_____ Break turn G. No armament remaining

_____ Hard Turn H. Attacker’s position relative to defender's 6 o’clock

_____ Joker I. Maximum performance, energy depleting turn

_____ Bingo J. Prebriefed fuel state required for safe recovery

_____ Tally K. Turn to deny weapons parameters

_____ No Joy L. Bandit not in sight

_____ Blind M. Leader or wingman not in sight

_____ Visual N. Energy maintaining turn

_____ Winchester O. Turn initiated ahead of the 3/9 line to reduce heading crossing angle

_____ Engaged P. Leader or wingman in sight

8. List thirteen reasons to KIO or terminate a BFM engagement.

1. ______________________________ 9. _____________________________

2. ______________________________ 10. _____________________________

3. ______________________________ 11. _____________________________

4. ______________________________ 12. _____________________________

5. ______________________________ 13. _____________________________

6. ______________________________

7. ______________________________

8. ______________________________