Fighter Debrief Culture

Captain Rob Teschner’s paper The Vocabulary of the Mission Debrief, USAF Weapons Review, Summer 2005.

Introduction

The debrief is designed to focus analysis on either the accomplishment or failure to accomplish desired learning objectives (DLOs) and/or mission objectives. Mission objectives drive the planning or execution items that must be accomplished to be successful and therefore expose the areas of individual, crew, or team performance that must be addressed to correct for future iterations.

Any effective debrief identifies errors and provides fixes for those errors, while also allowing those who did not directly commit a given error the advantage of learning from others’ mistakes. Since there is not enough time for each operator to make all the mistakes, this type of learning creates efficiency by reducing repetitive errors across the group that is present for a given debrief.

The fighter aviation community has refined its debrief process over several decades; it is fundamental to fighter culture. Any organization can utilize fighter debrief concepts as a reference—or even baseline—to develop its own culture of debrief.

Fighter Debrief Culture

To understand fighter debrief culture in a way that helps, it is important to describe that fighter culture in its native context. Debrief has always been an important part of fighter aviation culture, facilitating honest and direct feedback on every mission element.

Work-life balance and operations tempo require debriefs to be direct and succinct, due to the limited time available after mission planning, briefing, and flying the mission. By the time the debrief starts, 455 members are likely already running out of time.

To maintain focus and aid efficiency, debriefers commonly use the mantra “Plan, Products, Brief, Administration, Tactical Admin, and Execution” to address all portions of the mission.

At the beginning of the debrief, it is helpful to keep sections like “Brief” as simple as possible by asking, “was there anything from the brief negatively affecting your execution today or that you have questions on?” Directing this question to the room allows the debriefer to quickly address pre-execution issues, and then move to the mission itself. However, the brief may have negatively affected execution in a way that remains to be determined in debrief, so it should also be considered during the debrief focus point (DFP) development. Utilizing this debrief structure, the debriefer quickly addresses issues in each pre- and post-execution section with the flight participants until arriving at mission execution. Mission execution review is designed to focus the debrief so each person can improve for the next mission. This does not mean each person gets individually debriefed, but rather that those who made errors most impactful to mission success or failure have those errors identified and corrected in a way everyone can learn from them. All participants should leave understanding how to better execute the mission.

An additional key to ensuring efficient and effective debrief is withholding personal feelings and ensuring seniority does not impede instruction for correctable mistakes. Debrief attendees should behave professionally, and critiques of execution should not be personal in nature, nor taken personally by flight participants. Aircrew must avoid defensive attitudes and cannot make excuses for poor performance. To this end, mission reconstruction should focus on facts, so instructional fixes can be objective corrections to demonstrated errors. If crews take debrief points personally, or if pride stands in the way of learning, valuable lessons are lost.

The person running the debrief sets rules of engagement (ROE), which are designed to help avoid hurt feelings and pride issues. ROE can vary depending on the squadron and the person in charge of the debrief. Below is an example of debrief ROE, developed over several years of flying fighter aircraft. Although not all-inclusive, it provides a good starting point.

Debrief ROE

- Debrief the mistake not the person; do not make it personal.

- There is no seniority in the debrief.

- That does not mean you can say whatever you want.

- Keep it professional, even if you don´t do this for a living.

- No hurt feelings allowed.

- Do not let pride stand in the way of learning.

- Do not take the debrief personally. It is not an attack; it is targeted learning.

- Answer yes or no questions with "yes or "no".

- The debriefer is collecting data to make an informed decision to identify the DFP.

- So, when asked a question, directly answer that question.

- Do not make excuses.

- Resist the urge to explain/defend yourself.

- Never miss an opportunity to shut up and listen.

- Be on time and have the required information available.

- Take notes.

- It's been a long day - write down important items to review before your next event.

- Write down questions to ask, or to research after the debreif.

- When running a debrief, it is acceptable to say "I do not know the answer to that; lets look that up together after the debrief."

- Do not make up an answer.

- Do not let your arrogance get in the way of someone else's learning.

- Be efficient with peoples time.

- Do not waste time trying to look good; get to the point and move on.

- Debrief is not a stage to show off your knowledge; it is to improve yourself and those around you.

- Learn as much as possible.

- Learn one thing and teach one thing every time.

Different communities have passed down similar rules throughout the years, and everyone has their favorite—or most important—rule. Another helpful source is an article written for the Judge Advocate General’s (JAG’s) corps by Major Mark Perry (an F-15C pilot) and Major Benjamin Martin (a JAG officer). Their five key rules offer great insight into a portion of the debrief process. They lay an initial foundation that helps underpin the essence of the debrief: an investigation into the errors made. The overall goal is to show the facts of what occurred in order to ascertain, prove, and teach the fix (i.e., a “lesson learned”) for everyone to internalize from the debrief. This type of debrief is only possible in the limited time available if everyone is honest about mistakes and is ready to learn.

Another critical facet to making this type of debrief possible is careful selection of who runs each debrief. It is important to develop a community standard. As a general rule, whoever established the desired learning objectives (DLOs) which drive the mission objectives should run the debrief. This is usually the same person who prepared the mission and gave the briefing. Ideally this is an instructor, unless someone is being upgraded, but it does not have to be. Especially important is the maxim that seniority has nothing to do with who runs the debrief. The squadron commander—or the wing commander—may be in the formation, but the day’s lead or instructor is the most appropriate to lead assessment of facts and fixes. In that same vein, there is no seniority in the debrief. Per the ROE, this does not mean one can say whatever he/she wants. Always remain professional. This helps establish a respectful balance, while taking advantage of the reality that learning can come from anyone, regardless of rank.

The Process

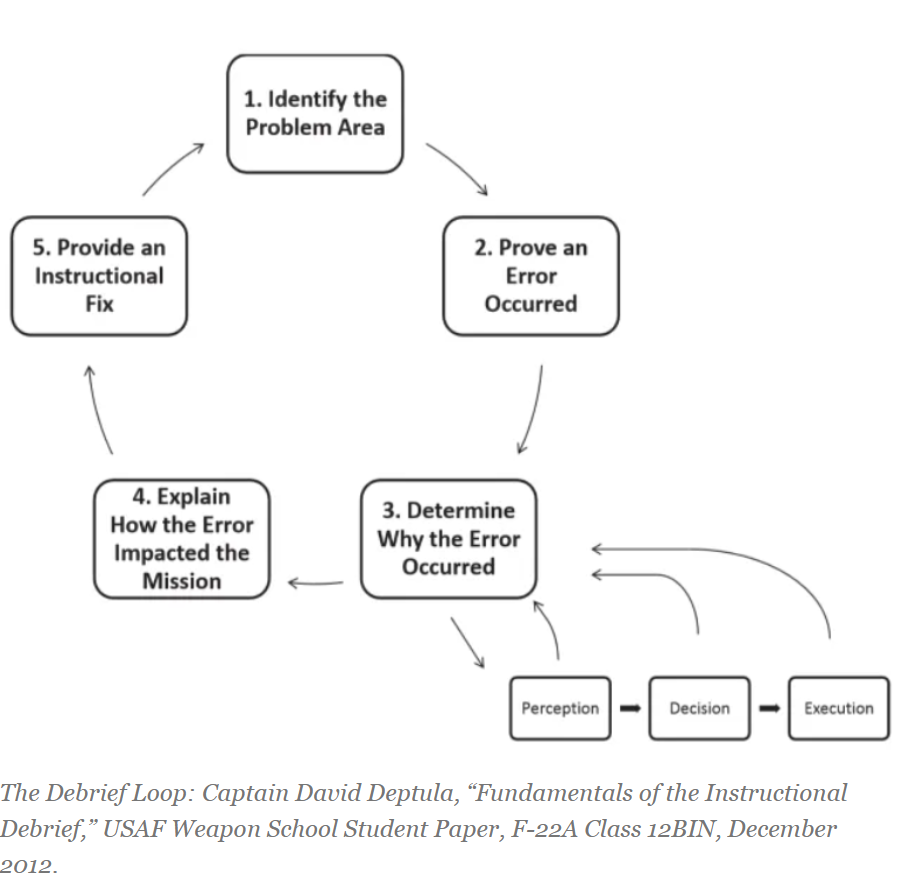

The USAF Weapons School (i.e., Weapons Instructor Course or WIC) utilizes a debrief standard across all the school’s platforms. The mission analysis process assesses accomplishment of the DLOs. If a formation fails to accomplish a specific DLO, the process then identifies the errors that led to the failure. These errors become DFPs or learning points (LPs), the former having a more significant impact on mission success than the latter. Once the debriefer identifies the DFP(s) or LP(s), he/she categorizes it/them into one of three areas: perception, decision, or execution. After error-categorization, the debriefer then provides an instructional fix to maximize learning and to ensure those present can make a tangible change or correction for future missions. Combining a DFP with an instructional fix results in a lesson learned—the critical element to community improvement.

DFPs and LPs should be the focal point of the debrief because they distill vast amounts of data into concise and effective lessons for each participant. If the debriefer does not identify the DFP or LP, untargeted analysis of the minutia can subjugate debrief focus, and those listening can lose interest or get confused. A debriefer identifying every minor error someone makes might not only waste valuable time, it can also serve to browbeat an individual, often leading to mental shutdown and an inability to actually learn. Instead, DFPs developed from the DLOs prevent aimless rambling and give the debrief focus. The debriefer identifies the DFPs during the reconstruction portion of the debrief. Whereas DFPs are failures in mission or tactical objectives (i.e., DLOs), learning points are when the formation accomplishes the DLO in spite of significant mistakes, or in a non-traditional way (e.g., the formation was able to complete the mission but made significant errors that can be debriefed). Learning can come from successes, using LPs, or from failures, identifying LPs and/or DFPs. In any of these three cases, the DFPs and/or LPs provide a common reference point and keep the debrief focused and succinct.

While the fighter community uses the mantra “Plan, Products, Brief, Admin, Tactical Admin, and Execution” to ensure all portions of the mission are addressed, another simple process applicable to any type of event is the five questions Air Force pilot Bill Crawford discusses in his 2015 TEDx Talk. These questions outline an easy-to-remember checklist to guide debriefs:

- What happened?

- What went right?

- What went wrong?

- Why?

- What are the Lessons Learned?

Step one: “What happened” is the process of validating the mission and tactical objectives. In other words, did the flight accomplish the DLOs?

Step two: “What went right” is an important part of the debrief process for two reasons. First, a debrief should not be just negative; and second, it is always good to use this step to show the group how things are supposed to look—it is motivating, reinforces good habits, and gives people something to replicate. Additionally, sometimes optimal execution is accomplished without recognition or by unintentional action, and should be highlighted to ensure understanding for application in the future.

Steps three and four: “What went wrong” and “why” is where the debrief loop, discussed below is utilized. Step three is not merely focused on “who made the mistake.” Similarly, step four is “why” not “who.” Referencing the aforementioned debrief ROE, do not make the debrief personal.

Step five: “What are the lessons learned” relates back to DFP and LP development; however, this discussion should be carried further, as described in Bill Crawford’s TEDx Talk. Incorporate lessons learned into the next execution cycle’s planning process. This process allows a wider group of people to learn from the debrief, growing the community as a whole.

When used properly, the debrief loop ensures DFPs and LPs are identified and fixed. Air Force then-Captain David Deptula formally described the debrief loop in his Weapons School Paper “Fundamentals of the Instructional Debrief.”

Determining why the error occurred is a vital part of debrief and is unfortunately where most debriefers have trouble. The tendency is to make an assumption on why someone made an error and then give them a fix to that assumption. However, when the person running the debrief utilizes the third step of the debrief loop correctly, he/she asks direct questions of the person who made the mistake to get to the “why” of the error. This is where it is important that all participants of a debrief adhere to rules four and five of the Debrief ROE:

4. Answer yes or no questions with "yes or "no".

- The debriefer is collecting data to make an informed decision to identify the DFP.

- So, when asked a question, directly answer that question.

5. Do not make excuses.

- Resist the urge to explain/defend yourself.

When determining the “why,” the debrief loop recommends the use of the P/D/E model—Perception, Decision, and Execution. Using this model, the debriefer asks the correct questions to accurately determine the “why.” The person running the debrief should ask questions which categorize the error in perception, decision, or execution and then use that information to deliver an instructional fix (IF). An IF should be easy to follow and easy to implement in future missions.

No comments to display

No comments to display