FM-2 Tactical Formation

Tactical Formation

Objectives

1. Identify the key factors that determine the type of tactical formation to be flown.

2. Identify the correct flight lead and wingman deconfliction responsibilities when maneuvering in a tactical formation.

3. Given a specific tactical situation, identify the correct T-38C visual lookout responsibilities.

4. Identify the correct T-38C line-abreast parameters and the appropriate procedures to solve out of position errors.

5. Identify the correct procedures to accomplish line-abreast turns.

6. Identify the uses of fighting wing and how to correctly fly the position.

7. Identify the uses of wedge and how to correctly fly the position.

8. Identify the correct purpose and basic geometry of various three-/four-ship tactical formations.

9. Describe the heat to guns exercise.

Assignment

1. Review FM–2 in the Formation Student Guide, B/F-V5A-K-FM-SG.

2. Review Interim T-38C Procedures Manual, Chapter 6, Section 6C, Tactical Formation through Section 6E,

Formation Abnormal Operations.

3. Review squadron standards.

Information

Tactical Formation Factors

Objective 1 — Identify the key factors that determine the type of tactical formation to be flown.

1. The primary purpose of tactical formation is to provide an offensive capability while maintaining security against attack by enemy air defenses.

2. Offensive formations stress ease of maneuvering and attack capability.

a. The formation with the most offensive potential gives the wingman time to use the weapons system and a clear field of fire.

b. Offensive formations vary from line-abreast to trail depending on weapons system and tactics.

3. Defensive formations stress mutual support (visual cross-coverage). In most cases the most defensive formation would be line-abreast.

4. Factors that determine the type of tactical formation to be flown in a given tactical environment include

a. the threat.

b. the mission.

c. the weather.

d. visibility restrictions of your aircraft.

e. number and type of aircraft.

f. maneuverability of the aircraft in the formation.

g. fuel situation.

h. aircraft weapons capability.

Deconfliction

Objective 2 — Identify the correct flight lead and wingman deconfliction responsibilities when maneuvering in a tactical formation.

1. Collision avoidance is the responsibility of the wingman during formation maneuvering. Unless directed by the flight lead, wingmen should maneuver to keep lead in sight.

2. The initial responsibility for deconfliction only transfers to the flight lead when

a. tactical maneuvering places the leader in the wingman’s blind cone or forces the wingman’s primary attention from the leader.

b. a wingman calls “BLIND.”

c. a wingman calls “PADLOCKED.”

3. Primary responsibility transfers back to the wingman when the wingman regains a visual on lead.

Visual Lookout

Objective 3 — Given a specific tactical situation, identify the correct T-38C visual lookout responsibilities.

1. Basic lookout rules

a. Each pilot must search the entire FOV, with special emphasis on briefed areas of responsibility.

b. The particular formation dictates the areas of responsibility.

c. Pilots should not concentrate lookout near the horizontal plane of the formation.

d. Pilots should not forget the requirement to search 12 o’clock, especially with the advent of all-aspect enemy weapon systems.

e. Two-seat aircraft should divide the visual lookout responsibility. Do not padlock both aircrew members on the same bandit(s).

f. The use of a dark helmet visor or sunglasses may reduce visual acquisition and detection range.

2. Two-ship line-abreast

a. The main advantage of the line- abreast formation lies in its potential for mutual visual cross-coverage.

b. Time spent searching for threats must be apportioned with reference to aircraft capability and the potential threat.

c. Visual lookout responsibilities must be clearly outlined and strong flight discipline must be exercised to ensure effectiveness.

d. Avoid random gazing and focus on a distant object. Once focused, various search patterns may be used (vertical, horizontal, etc.) depending on individual preference. No more than a 30º segment of the search area should be scanned at one time.

e. After 20 to 30 seconds, the eye focal distance drifts back to a point less than 10 ft away. Before this occurs, refocus and search another segment.

f. Visual detection depends upon factors such as aspect angle, atmospheric conditions (haze, smoke, moisture), background, and the condition of your helmet visor and canopy.

g. Flight leads and wingmen should consider sun angle, visibility, camouflage, weapons, ECM, etc., when maneuvering in tactical formation.

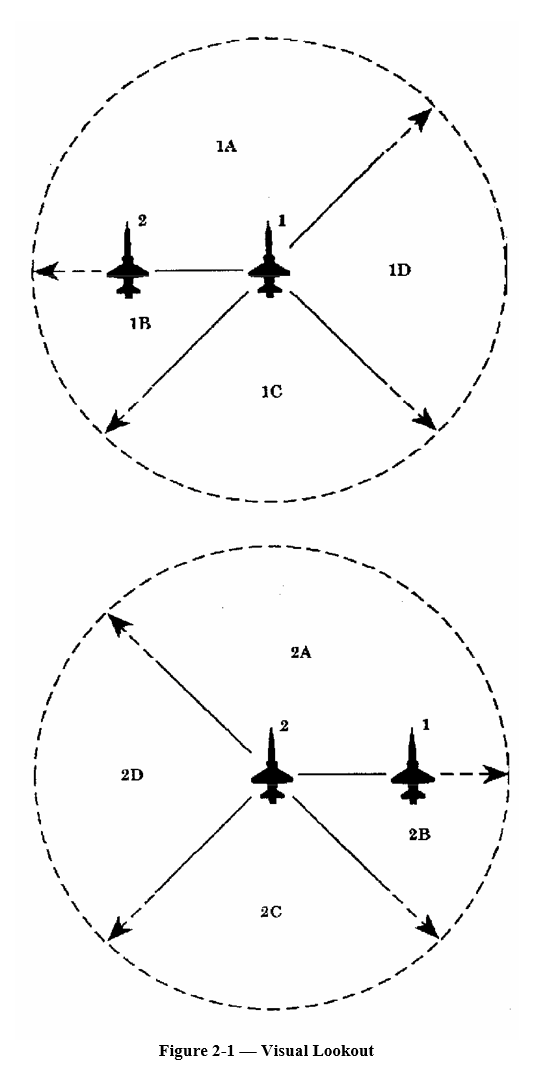

3. Scan pattern (Figure 2-1)

a. Lead’s scan pattern is divided into four sectors: 1A, 1B, 1C, and 1D with 1A having the highest priority and 1D the lowest.

b. The wingman’s scan pattern mirrors lead’s scan pattern for cross-coverage.

Line-Abreast

Objective 4 — Identify the correct T-38C line-abreast parameters and the appropriate procedures to solve out of position errors.

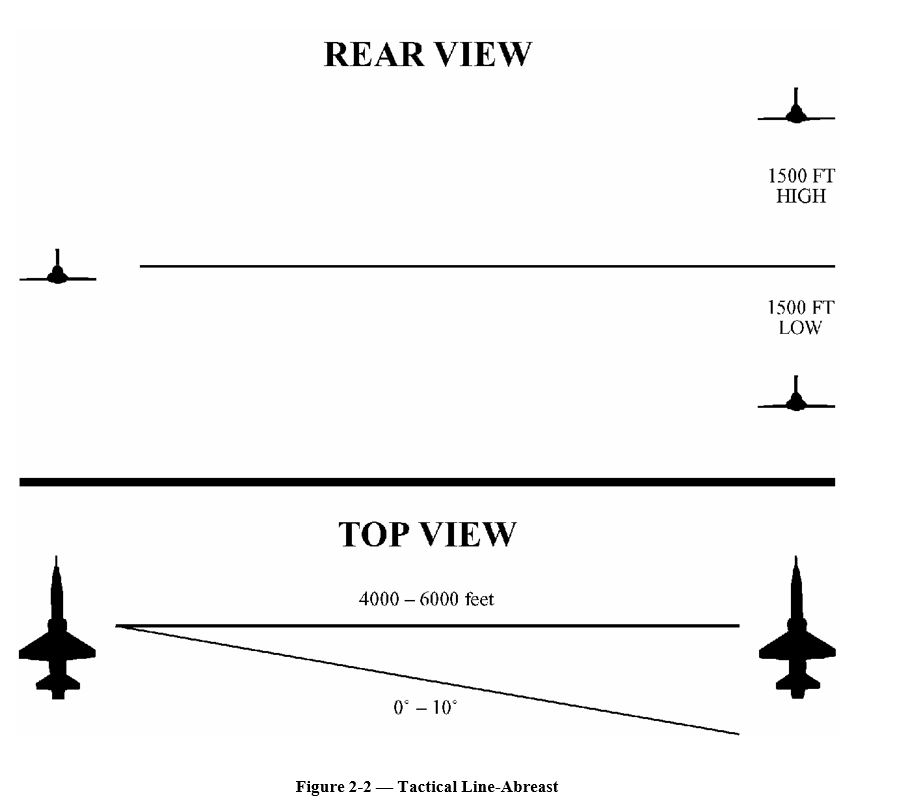

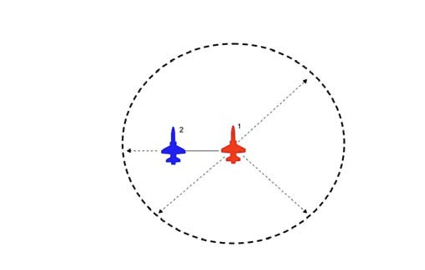

1. Parameters are described in Interim T-38C Procedures Manual, Chapter 6, (Figure 2-2).

a. Zero to 10º aft of line-abreast — A visual reference is lead abeam the rank on the wingman’s shoulder.

b. 4,000-6,000 ft lateral spacing

(1) At 4,000 ft the canopy bow disappears and both canopies blend into one.

(2) At 6,000 ft the canopies blend in with the aircraft.

(3) Outside 6,000 ft the burner can disappears.

c. 1,500 ft vertical stack — Use a known altitude block to calibrate your eyes to various stack positions.

2. Wingman priority is to regain the proper fore and aft position, lateral spacing, and vertical spacing (in that order) while maintaining tactical airspeed.

3. Corrections

a. Maintain formation by cross-referencing your flight lead but don’t stare at the aircraft.

b. Aggressively use the vertical to maintain line-abreast.

c. When using check turns to correct lateral spacing, you should roll wings level to see if the correction worked.

d. Always strive for a good vertical stack. It will pay off in the tactics arena. Diverging and converging flightpaths are also easier to see when in a good vertical stack.

4. Errors:

a. Flying more than 10º aft of line-abreast, or well ahead of line-abreast.

b. Failure to correct for a too wide or too close position.

c. Failure to see converging/diverging flightpaths.

d. Improper flight control inputs or improper power modulation.

e. Stares at flight lead; ineffective visual lookout.

Line-Abreast Turns

Objective 5 — Identify the correct procedures to accomplish line-abreast turns.

1. Basic maneuvering of the formation requires check turns, 45º, 90º, and 180º turns.

2. The commands for these turns may be signaled by radio call or, in a radio silent environment, through lead’s turns/wing flashes.

3. Visual search during turns

a. If flight members don’t cross flightpaths, as in a check turn, visual responsibilities do not change.

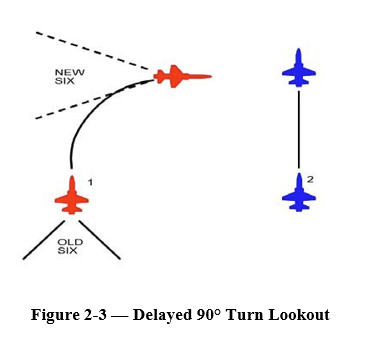

b. For 45º and 90º turns, the turning fighter checks the old six and the stabilized fighter checks the new six (Figure 2-3).

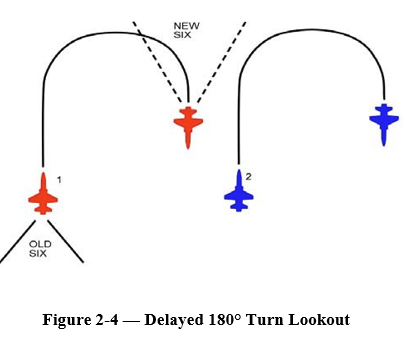

c. For 180º turns, visual search is complicated since both fighters are maneuvering simultaneously. The new six area, 12 o’clock to the turn, should be cleared visually. Once the turn is started, both flight members should concentrate on their common six, particularly the trailing aircraft (Figure 2-4).

4. Turn contract

a. MIL power.

b. 4-Gs or light buffet.

c. Briefed airspeed.

d. Know squadron standards.

5. Check turns

a. A check turn is a simultaneous turn by both fighters to a heading less than 45º from the original heading. Check turns are primarily used for navigation corrections or to help the wingman regain line-abreast formation.

b. After turn completion, flight members should use the vertical to regain line-abreast.

c. At low altitude, the flight should regain line-

abreast by using throttles, making short lateral corrections, or by having the front fighter shackle across the nose of the trailing fighter.

Figure 2-4 — Delayed 180° Turn Lookout

6. Delayed turns

a. Purpose

(1) The delayed turn is used to turn a line- abreast formation while maintaining lookout.

(2) It allows both the new and the old 6 o’clock areas to be searched; however, mutual support is degraded during the turn.

b. Radio silent maneuvering “charter”

(1) The wingman strives for the briefed formation position.

(2) Lead initiates all turns.

(3) All turns are assumed to be 90º unless signaled otherwise.

(4) If the leader turns back into the wingman’s turn, the wingman rolls out.

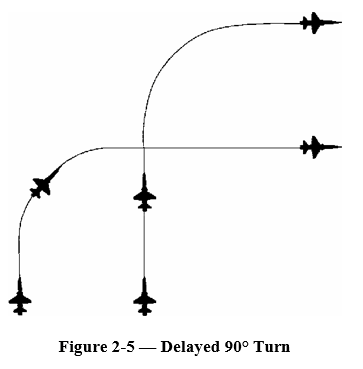

c. Delayed 90º execution (Figure 2-5)

(1) Know comm-out visual signals.

(2) The leader initiates the delayed 90º turn using a prebriefed signal.

(3) The outside fighter starts a turn at prebriefed parameters to the determined heading.

(4) The inside fighter, initiates a contract turn just prior to looking down the outside fighters intake or after seeing a rapid increase in the outside fighters LOS rate. Both these references should occur after the outside fighter has turned approximately 45º.

Figure 2-5 — Delayed 90° Turn

(5) If out of position, vary the timing and G loading of your turn. Generally, when you are too close or too far aft, begin the turn earlier; when you are too wide or too far forward, begin the turn later.

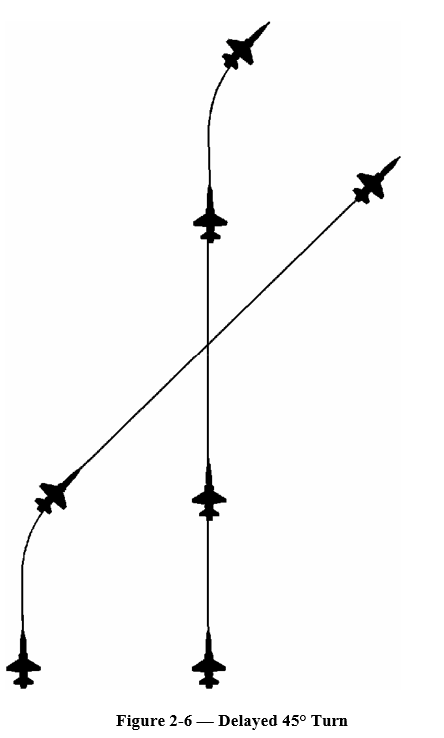

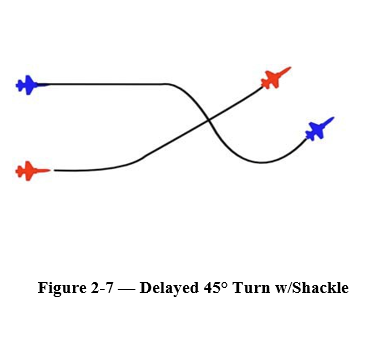

d. Delayed 45º execution (Figure 2-6 and 2-7)

(1) Know comm-out visual signals.

(2) The delayed 45º turn is accomplished in much the same manner as a delayed 90º turn except that the inside fighter delays longer to achieve the desired lateral separation at roll- out.

(3) To reduce the time required to complete the delayed 45º turn, the inside fighter can shackle.

e. Delayed turn errors

(1) Failure to follow contract, i.e., improper G, power, airspeed control.

(2) Failure to see delayed turn visual signal.

(3) Starts turn too early or too late.

(4) Improper lift vector control during turn.

(5) Loses sight of lead.

(6) Uses HSI instead of lead for primary turn point reference.

(7) After turn completion slow to correct if out of position.

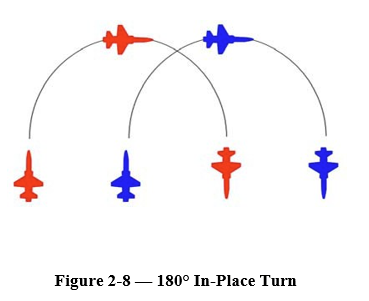

7. In-place turns (Figure 2-8)

a. Purpose

Figure 2-6 — Delayed 45° Turn

Figure 2-7 — Delayed 45° Turn w/Shackle

(1) Generally, in-place turns, also referred to as “hook” turns, are used to quickly turn a line-abreast formation 180º.

(2) In-place turns may be used for other than 180º turn reversals. For example, they can be used to convert to or from a trail/ staggered position to line- abreast.

(3) The primary disadvantage is the loss of visual cross-coverage on the trailing fighter during the turn.

b. Execution

(1) A wingflash away from the wingman is the comm-out visual signal.

Figure 2-8 — 180° In-Place Turn

(2) Both aircraft simultaneously execute a hard turn at prebriefed parameters.

(3) If the turn is to the right, the fighter on the right leads the turn for 90º, with the fighter on the left matching the turn and maintaining flightpath clearance.

(4) At the 90º point, responsibilities switch as relative positions (left and right) change.

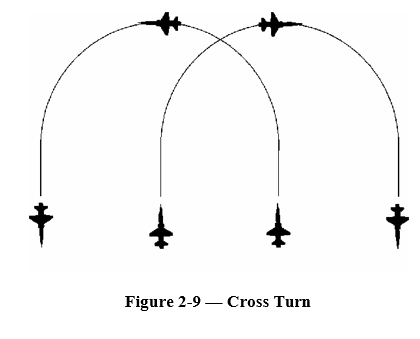

8. Cross-turns (Figure 2-9)

a. Purpose

(1) This turn is another 180º reversal option.

(2) During the turn into, a line-abreast formation can maneuver to a prebriefed deployed formation.

(3) The formation may be vulnerable after the fighters pass due to the loss of visual cross-coverage and mutual support potential. In a very low altitude environment the cross-turn is difficult to perform.

b. Execution

(1) On verbal command, both aircraft simultaneously execute a hard turn into each other.

(2) Aircraft should cross after 60º to 90º of turn and continue to turn through 180º.

(3) Wingmen are responsible for deconfliction and should maneuver above the flight lead at low altitude.

(4) Always maintain ground clearance and after passing each other; both aircraft should strive to stay visual.

Figure 2-9 — Cross Turn

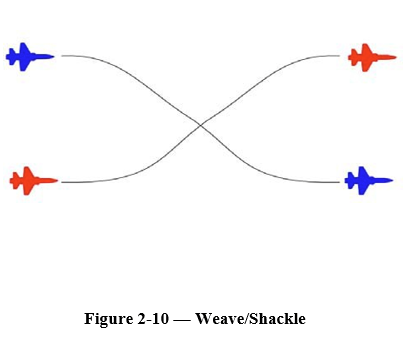

9. Weave/shackle — Maneuvers which may be used to regain line-abreast formation, place the wingman on the opposite side of the formation, escort a slower aircraft, or attempt to confuse the opposition (Figure 2-10).

a. Weave — Continuous crossing of flightpaths.

b. Shackle — One weave; a single crossing of flightpath; maneuver to adjust/regain formation parameters.

c. Execution

(1) On verbal command, both aircraft simultaneously execute a hard turn into each other.

(2) After approximately 45º of turn, each aircraft should reverse the direction of turn to the original heading. At low altitude, the wingman will deconflict high. During a weave this maneuver will be repeated until the leader rolls out and maintains a constant heading.

Figure 2-10 — Weave/Shackle

(3) Normally, if one aircraft is more than one clock position aft of line-abreast and a weave is called, that aircraft will maintain heading as the forward aircraft shackles to regain line-abreast formation.

Fighting Wing

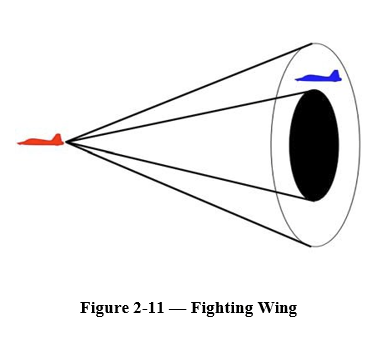

Objective 6 — Identify the uses of fighting wing and how to correctly fly the position.

1. Purpose — This formation gives the wingman a maneuvering cone aft of line-abreast. It is employed in situations where maximum maneuvering potential is desired.

2. Position — The maneuvering cone will be IAW Interim T-38C Procedures Manual, Chapter 6. The cone may be further specified in local squadron standards or as briefed by the flight lead (Figure 2-11).

3. Advantages

a. Fighting wing allows the element to maintain flight integrity under marginal weather conditions or in terrain when the prebriefed formation cannot be maintained.

b. Allows for cockpit heads-down time for administration functions when in a low-threat arena where hard maneuvering is not required.

4. Disadvantages

(1) Poor to nonexistent 6 o’clock coverage.

b. Detection of formation by single threat.

5. Execution

Figure 2-11 — Fighting Wing

a. Number two maneuvers off lead with cutoff as necessary to maintain position.

b. The correct fighting wing position is rarely static.

c. Wingmen should only be directly aft of lead when crossing from one side to the other.

d. Plan to cross above or below lead’s jetwash. Unload the aircraft if you can’t avoid the jetwash.

e. Know squadron standards.

6. Errors

a. Improper parameters.

b. Improper lift vector control.

c. Improper power modulation.

d. Inappropriate cutoff.

e. Losing sight.

Wedge

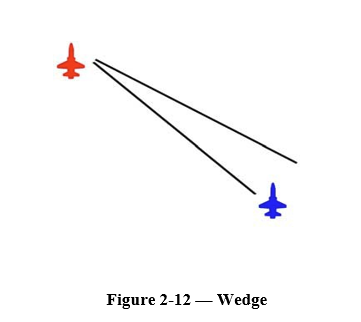

Objective 7 — Identify the uses of wedge and how to correctly fly the position.

1. Purpose — Considering the variety of air and surface threats, terrain, weather, target arrays, and mission objectives that will be encountered in carrying out a wide range of wartime taskings, there is a need for both line-abreast and wedge formations.

2. Position — The maneuvering cone will be IAW Interim T-38C Procedures Manual, Chapter 6. The cone may be further specified in local squadron standards or as briefed by the flight lead (Figure 2-12).

3. Advantages

Figure 2-12 — Wedge

b. Lead changes from wedge are difficult to execute.

5. Execution

a. Wedge formation can be flown successfully at low altitude, especially in mountainous terrain, because the wingman can keep both the leader in sight and adequately scan approaching terrain.

b. Wedge formation also allows for good offensive air capability against a forward quarter threat and allows good maneuvering potential.

c. Wedge formation also provides much greater maneuvering flexibility than line-abreast as the wingman handles turns of any magnitude by maneuvers in the cone on either side of the leader.

4. Disadvantages

a. Wedge formation provides little to no 6 o’clock protection for the wingman.

a. The wingman may switch sides as required during turns.

b. The wingman may also switch sides as required to avoid terrain, obstacles or weather but should return to the original side unless cleared by the leader.

6. Errors

a. Improper parameters.

b. Improper lift vector control.

c. Improper power modulation.

d. Inappropriate cutoff.

e. Flying below lead’s AGL altitude.

f. Losing sight.

Three/Four-Ship Tactical

Objective 8 — Identify the correct purpose and basic geometry of various three-/four-ship tactical formations.

1. Purpose — The four-ship formation concentrates firepower, increases mutual support, and multiplies tactical options.

a. The four-ship is under control of the flight lead and is employed as a single entity until such time as it is forced to separate into two elements.

b. At no time should an element sacrifice element integrity attempting to maintain the four-ship formation.

c. Each element should have its own radar and visual plan so that no changes will be required if the four-ship is split into two-ships.

2. Basic contract

a. Numbers two and four maneuver off their element leader.

b. As tactical formations increase in size, wingmen must maintain formation on their element lead. During turns, it is especially important that wingmen keep situational awareness on other flight members as well.

c. Normally, formation visual signals performed by a flight/element leader pertain only to the associated element unless specified otherwise by the flight leader.

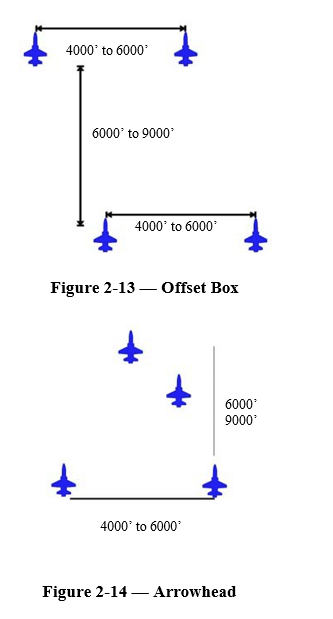

3. Box/offset box (Figure 2-13)

a. In the box formation, elements use the basic line-abreast two-ship maneuvering and lookout principles.

b. The trailing element takes 1 to 1.5 NM separation, depending on terrain and weather.

c. Because the T-38C is difficult to see from a direct trail position, a slight offset will facilitate keeping sight of the lead element. At low altitude, a high stack by the lead element may also aid rear element visual lookout.

d. Advantages

(1) The formation provides excellent mutual support and lookout.

(2) The rear element is positioned to engage an adversary making a stern conversion on the lead element.

(3) It is difficult to visually acquire the entire flight.

(4) Element spacing for an attack is built into the formation.

e. Disadvantages

(1) The formation is difficult to fly in poor visibility and rugged terrain.

(2) Depending on position, the trailing element may be momentarily mistaken as a threat, especially if staggered too much off to one side.

f. Execution

(1) Delayed turns from the box/offset box are executed as if there were two independent two-ship elements, except the rear element attempts to fly either the same or a parallel groundtrack to the lead element.

(2) Applying deconfliction rules and utilizing air-to-air TACAN will greatly reduce the possibility of a conflict and improve visual acquisition between elements.

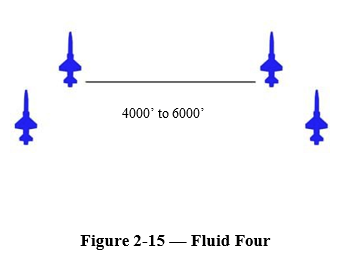

g. The arrowhead variation makes number two’s formation easier, freeing the pilot for more lookout (Figure 2-14).

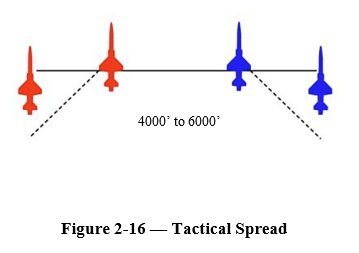

4. Fluid four (Figure 2-15)

a. Element leads maintain line-abreast formation, while wingmen assume fighting wing.

b. Number two and number four maneuver off their element leaders and to the outside of the formation.

c. Advantages

(1) Inexperienced wingmen are kept close for ease of maneuvering.

(2) Four-ship maneuverability is good.

(3) Formation provides concentration of force.

(4) Easily converts to three-ship when one aircraft falls out.

d. Disadvantages

(1) Adversary can acquire all four aircraft.

Figure 2-15 — Fluid Four

(2) Defensive maneuvering rapidly becomes confusing due to the proximity of aircraft.

(3) Cumbersome to maneuver at low altitude in rough terrain.

e. Execution

(1) Element leads perform comm-in or comm-out turns as if they were a two-ship.

(2) Wingmen should attain a good vertical stack. Doing so will make adversary acquisition more difficult and aircraft deconfliction less difficult.

(3) Wingmen should keep situational awareness on the opposing element.

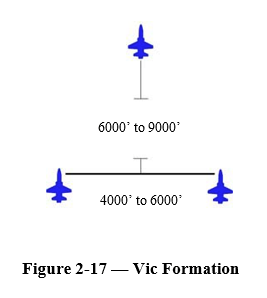

5. Tactical spread (Figure 2-16)

a. Tactical spread maximizes firepower for BVR weapons employment.

b. Tactical spread may be referred to as a “Wall” when all aircraft are line-abreast.

c. The elements are not always required to be line- abreast. On some occasions they may be briefly in trail. A box/offset formation could be maneuvered to spread and vice versa.

d. Advantages

(1) Offensive firepower.

(2) Good visual lookout.

(3) Change leads without major repositioning.

Figure 2-16 — Tactical Spread

(4) Difficult for an adversary to visually acquire the entire flight at once.

e. Disadvantages

(1) Maneuvering is difficult if the line-abreast position is maintained.

(2) Very difficult for wingmen to fly at low altitude.

f. Execution

(1) Delayed turns are executed just as they were in two-ship tactical.

(2) On lead’s command, the aircraft on the outside of the formation initiates a 90º turn into the formation.

(3) The next aircraft on the outside of the formation uses the standard two-ship visual reference to start the turn.

(4) This procedure is used until all aircraft have completed the turn.

6. Three-ship formations

a. Purpose

(1) There may be occasions when a priority mission requires maximum available aircraft and a three-ship is the only alternative.

(2) Mutual support requirements to ensure survivability are paramount; therefore, a three-ship contingency should be briefed on all four-ship missions.

b. Vic formation — The offset box/arrowhead four-

Figure 2-17 — Vic Formation

ship without number two (Figure 2-17).

(1) The lead aircraft maneuvers as desired.

(2) The trailing element uses line-abreast maneuvering to follow.

c. Fluid three — Same as fluid four with one airplane missing.

(1) Normally if lead falls out, #3 assumes lead and #2 moves to line-abreast.

(2) Normally if #3 falls out, #4 moves up to line-abreast.

(3) If #2 or #4 fall out there are no changes.

d. Three-ship spread — The same as spread four with one aircraft missing. Roles and responsibilities caused by fall out are the same as fluid three.

7. Three-/four-ship tactical errors

a. All members must discipline themselves to execute precisely as briefed.

b. Two-ship errors are magnified in larger formations. For example, if #2 drops 30º aft of line-abreast while flying offset box and lead directs a turn, then a conflict between the two elements can develop. A breakdown in mutual support also occurs.

c. A delayed blind call can be deadly with regard to mutual support and aircraft deconfliction.

d. Low wingmen SA — Increased formation numbers can saturate inexperienced wingmen.

Heat to Guns Exercise

Objective 9 — Describe the heat to guns exercise.

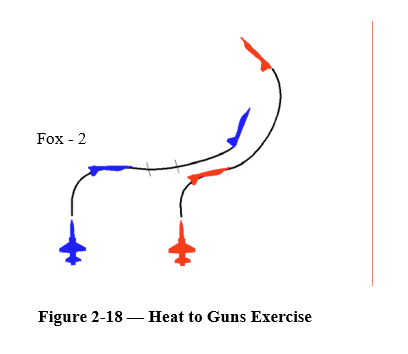

1. Exercise goals — The student will maneuver from line abreast, tactical formation to the AIM-9 WEZ and follow-on gun WEZ (Figure 2-18).

2. Heat-to-guns execution

a. Start with proper parameters!

b. As target turns away from attacker, the attacker performs a max performance turn into the target.

c. As your turn brings the target toward the “missile diamond” ease off the turn and put the target in the seeker field of view and pickle (track for one/third second post pickle).

d. After the Fox-2, the attacker will reposition to the

guns WEZ and practice gun employment (pursuit curves will be discussed further in AA-4).

e. Gun track 1,000 — 2,500 ft, with pipper on target in- plane. Control closure and maintain 1,000 ft bubble awareness.

3. Heat to guns errors

a. Improper starting parameters, switchology

b. Improper lift vector, G, power control

c. Invalid Fox-2

d. Continues to point at target after Fox-2

e. Fails to control closure during reposition to guns or stagnates.

f. Fails to avoid jetwash and/or target bubble

g. Unstable/poor target tracking

Figure 2-18 — Heat to Guns Exercise

Review Exercise 02

Complete the following review exercise. Answers are in the back of the SG.

1. Offensive formations stress ease of maneuvering and attack capability. While defensive formations stress mutual support. In most cases the most defensive formation would be .

2. The flight lead becomes responsible for deconfliction when tactical maneuvering places the leader in the wingman’s “blind cone”, the wingman calls , or the wingman calls . Primary deconfliction transfers back to the wingman once the wingman acknowledges a visual on lead.

3. Label the following leader scan pattern from highest priority to lowest priority.

4. Which of the following lists identifies the correct wingman priority to regain proper tactical formation?

a. Correct lateral, then vertical, then fore/aft.

b. Correct vertical, then lateral, then fore/aft.

c. Correct fore/aft, then lateral, then vertical.

d. Correct lateral, then fore/aft, then vertical.

5. For the visual lookout during 45º and 90º turns, the turning fighter checks the and the stabilized fighter checks the .

6. Which of the following is/are part of the radio silent maneuvering charter?

a. The wingman strives for the briefed formation position.

b. All turns are assumed to be 90º unless signaled otherwise.

c. If the leader turns back into the wingman’s turn, the wingman rolls out.

d. Both a and b are correct.

e. All the above are correct.

7. True or False: If out of position during delayed turns, vary the timing and G loading of your turn. Generally, when you are too far aft or too close, begin the turn earlier; when you are too wide or too far forward, begin the turn later.

8. A away from the wingman is the comm-out in-place turn visual signal.

9. True or False: A cross-turn is easier to perform than an in-place turn at very low altitude.

10. During fighting wing, plan to maneuver above or below lead’s jetwash. the aircraft if you can’t avoid the jetwash.

11. True or false: The primary disadvantage of fighting wing and wedge formation is the poor to nonexistent 6 o’clock coverage they provide.

12. Normally, when flights of more than two aircraft are in tactical formation, formation visual signals performed by a flight/element leader pertain only to the associated unless specified otherwise by the flight leader.

13. During , element leads maintain line-abreast formation, while wingmen maneuver in fighting wing.

a. box/offset box

b. tactical spread

c. fluid four

d. Both b and c are correct.

No comments to display

No comments to display